press

June-July 1998 Articles:

<[cybersociety]>

Sex By Numbers

Your World

Quickies

(music reviews)

Confessions of A Phone Psychic

The Inconsistency of Theism

E-Mail UsYour Comments

Archives

Home

Many animals can use tools and technology to extend their reach and adapt their environment to their survival needs. However, only man can communicate complex series of information, and only man uses tools to communicate information beyond his immediate environment--and even beyond his own place in time.

From drum beating and hieroglyphics to modern electronics, man has used technology to expand his ability to convey information almost infinitely. With each new development in communication, his reach has broadened and his contact with cultures outside his own has expanded. It is obvious, for example, that the development of the printing press influenced culture by making it easier to document and store information and to move it quickly and efficiently from one community to another, expanding the boundaries of a culture beyond its immediate geographic limits.

What is not as obvious, however, is that the development of printing not only changed the information we received, but how we processed the information, as well. Gutenberg's press not only made it possible for more people to receive information, but it also made it possible to receive the information at our own convenience--to break it down and consume it piece by piece when we had the urge, rather than having to sit in a crowd with others and digest the dayıs ³lesson,² much in the way the VCR changed our television and movie viewing habits. In other words, our means of communication not only effects what we think, but how we think.

As print media became more and more common, radio, recording, movies, and television developed. Each, in its turn, affected the human mind, not only by affecting what we learned and what we thought, but by affecting how we received the information. The question of whether the content of media affects what we think has been asked for decades; in the Victorian era novels were believed to harm the morals of "ladies," and in the 1950's, it was suggested that pulp novels encouraged criminal behavior. Now, of course, we debate whether the content of music videos encourages teens to shoot each other.

Only in the last few years have people begun to wonder if communications media affect our thinking process. In 1995, for example, a group of educators advanced the theory that viewing television caused attention deficit disorder. Specifically, they suggested that children raised watching Sesame Street became so used to absorbing information in short, randomly-arranged doses that they could only process it in that way, thus rendering them incapable of learning in a traditional school environment.

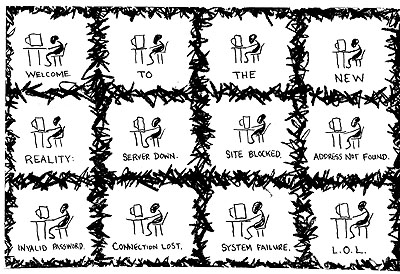

The latest communications medium, the Internet, probably will have an effect on our information-processing that will far exceed that of any previous technology. At this point, most people consider the information available online to be essentially an extension of print media. However, certain aspects of Internet-style communication make it much more than that. Online communication is as distinctly different from print media as television is from Peking opera.

The Internet, as a medium, is interactive. It allows us not only to absorb information at any time of day or night, but to decide in what way to receive it. Unlike standard, finite, linear print media, the information on the 'net is arranged globally. That is, through hypertext links, it's possible to follow the connections from one topic to another almost indefinitely.

The media have made much of the Internet's contributions to contemporary neurosis. In the last few years, numerous horror stories have appeared as front page news: a woman had her children taken away from her after locking herself and her computer in her bedroom for hours on end. Another left her husband and went into the Arkansas woods to willingly allow her online lover to torture her to death. Advice columnists frequently run letters from men and women whose spouses have left behind their homes, jobs, and families to be with their online lovers. And an obsession with cyber porn has disrupted the home lives and careers of countless otherwise productive members of society.

The condition has even led to a proposal that obsessive use of the Internet be considered a bona fide addiction. According to Kimberly S. Young, Ph.D., who first proposed diagnosing Internet Addiction, its victims seem to come in two varieties--those who are addicted to chatting, and those who are addicted to information. It may be hard to imagine becoming obsessed with information, but the way it is presented online, through a combination of multi-media and hypertext, may make it virtually impossible for some people to tear themselves away from the endless supply of information.

I used to sell office supplies. One day, a "different-thinking" man came into the store to shop for a filing system. He had a problem, and he wanted a solution--a filing system that would only allow him to directly access the information he went there for. It seemed that he was easily distracted by information. He would try to research something--like deer hunting regulations--and would see an article about the natural history of the deer, which would lead him look up a game refuge in Texas, which would lead to reading about the Alamo, which lead to the biography of Daniel Boone, and on and on. Hours later, he would still be reading, and still wouldn't have looked up deer-hunting regulations.

This is a perfect example of the way in which an information junky is led into spending hours online consuming information. The ability to link from one topic to another mimics the process of human thought and informal communication. Have you ever tracked the progress of an engrossing conversation with someone at a cocktail party? You begin discussing your job, and end up discussing UFOs--while along the way you've talked about religious cults, your kids' homework, and a dozen other, seeminly disparate topics. That's how HTML (web programming language) works.

The other aspect of online communication, "chatting," has an even greater potential for "addiction," or at least obsessive overuse. Beyond the "gee whiz" aspect of being able to chat casually with a stranger from the other side of the world as easily as you would someone on the next barstool, it has the potential to make each and every one of its users a small-time media celebrity and provides instant, risk-free socialization.

Internet addicts, whether chat junkies, porn junkies, or information junkies, tend to say the same things about their addiction--it's always available, and it offers instant gratification. However, what they don't seem to notice is that it offers the promise of instant gratification, which is even more addictive. It's like gambling: if someone goes to a casino and instantly wins, they'll continue to play. If they continue to win, they'll soon get bored and move on to something else. If they instantly lose, the behavior will extinguish quickly, too. However, if sometimes they win, and sometimes they lose, they'll keep playing for hours.

Behaviorists have noticed this effect with lab rats. If a rat pushes a lever and gets food, it pushes the lever when it's hungry. If it pushes the lever and gets nothing, it won't bother to push the lever at all. However, if sometimes the rat gets food when it pushes the lever, and sometimes it gets nothing, then the rat will push the lever over and over again, almost obsessively.

Internet chat and surf have similar effects on the human psyche. Sometimes the chataholic will find instant gratification--a new friend, a pleasant chat with an old friend, cybersex, or whatever they're looking for. Sometimes he won't. Sometimes the surfer will discover some interesting piece of information, some amusing web site, etc., and sometimes he won't. It's the unpredictability of it that keeps them coming back.

Many chat junkies admit that the anonymity of chatting is a big part of its appeal. Besides allowing one to say whatever they like without any really important consequences--getting slapped, for instance--it allows the chatter to be anyone he wants to be, at least for a few hours hanging out in his chosen cyber society. The effect is similar to a costume ball, where people can dress up to show off some hidden aspect of their personalities with which they identify. The cyber cowboys, vampires, and slinky vixens may be revealing some core aspect of their personalities that are in some ways "truer" than the façade their coworkers and family see. At the same time, their "character" can engage other characters in acting out fantasies that, even if it were possible, they would never experience in "real life."

Anyone who has ever been in an AOL chat room has seen the jerk enter who immediately begins asking for age, sex, and bra size, and announces for all to hear, "Any hot babes want to cyber?" The question would equate to entering a bar and asking "Who wants to fuck?" In some ways, the aforementioned jerk probably is demonstrating his true motivation. While he would more than likely be ashamed--or afraid of a punch in the nose--to ask loudly for sex in real-time public, he probably walks into a bar wondering which of the large-breasted women there he might score with tonight.

The questions become: Will this new technology, which favors non-linear, global styles of learning and communication, eventually create a society in which traditional linear learning has no place? Will the Internet ultimately relegate print media to an increasingly esoteric/elitist status, much as movies and television did to live drama? And will the lack of social sanctions against instant gratification-driven behavior encourage people to expect instant gratification in real time--to assume that within a few minutes of entering a bar, they can end up having sex with "any hot babe"?

The answer to all the above, of course, is "probably not." At least, not in the immediate future. More likely, the explosion of Internet usage indicates trends we already see--shrinking attention spans, a preference for more and more superficial information, and an increasing tendency to seek instant gratification. The important thing to know is that this is an important, highly unique medium, which combines a mass communications capability extending beyond even cable television with the intimate, one-to-one capability that will eventually exceed that of the telephone. More than any other, this medium has remained in the control of its consumers. As such, it has enormous power to change our society.•

Other articles by Morris Sullivan on this website:

- ArtsPolitic (April-May 1998)

- Human Cloning: Modern Prometheus or Frankenstein's Monster (Feb.-March 1998)