Issue Archives

Music Reviews

About IMPACT

Advertise in IMPACT

E-Mail Us

Join the Mailing List

Subscribe to IMPACT

Buy IMPACT T-Shirts

Links

Staff

Wanna Write for IMPACT?

Where to Find IMPACT

Home

A person with an eating disorder has an abnormal relationship with food; weight control is a constant battle, and eating is a source of anxiety. Food becomes a relief from stress and a means of controlling a life full of uncontrollable circumstances. Eating disorders, including anorexia, bulimia, binge eating and compulsive overeating, affect over two million men and women in the United States.

Bulimia is characterized by uncontrollable binge eating -- a large intake of food during a very short period of time -- followed by extreme efforts to compensate for the overeating. Binge eating does not mean "cheating" on your diet by having a couple of cookies; it's eating the whole bag of cookies and a gallon of ice cream, too. In studies on bulimia, researchers have found that on average, a binge-eater will consume about 3,400 calories in about an hour. In comparison, the normal caloric intake for a healthy, growing teenager is 2,000 to 3,000 calories per day.

After a binge, bulimics resort to a number of different measures to prevent weight gain. Some bulimics are characterized as the "purging" type; they either vomit or take laxatives and/or diuretics to avoid weight gain. Vomiting after bingeing is a way to immediately "undo" the damage that has been done and relieve the anxiety about the binge. This gratification subsides, only to be replaced by depression, guilt and shame. Taking laxatives or diuretics is another way to "purge" the body by expelling waste products to compensate for the food intake. Although laxatives and diuretics don't eliminate the calories or fat consumption, it still gives the bulimic a sense of relief.

There are also "non-purgers" -- bulimics who exercise excessively or fast. Fasting isn't continuous starving, as with anorexia; rather, the bulimic waits to eat for long periods of time to compensate for the binge. Non-purging bulimics may also restrict their eating, then compulsively exercise. In any case, weight control dominates the bulimic's life.

When I was in eleventh grade, my best friend was Debby, a pretty, blue-eyed blond. She was thin, yet obsessed with her weight -- Debby either ate too much or nothing at all -- and she'd always tell me how "fat" she was. Although I constantly told her she wasn't fat, she wouldn't listen. Her low self-esteem ultimately brought me down, too -- if Debby was "fat," but thinner than me, then what was I? If it was bad to be fat, then I was bad. I began focusing on my "imperfection," and my self-worth became solely dependent on my weight.

Debby eventually confessed to me that she had been vomiting on a regular basis to control her weight. Initially, I was repulsed by the idea, but when dieting wasn't working for me, it became a last resort in an attempt to restore my self-esteem. I soon began to spiral out of control.

To others, the person battling with bulimia may seem to be fine -- successful, well disciplined, intelligent and a high achiever. The feelings of inadequacy, anxiety and low self-esteem that accompany this disease may not be recognizable by others, making diagnosis difficult. And, bulimics are not necessarily bone-thin; in fact, most bulimics are normal weight, while others are slightly overweight, and may even be obese, so determining if a family member or friend is bulimic may be hard. Additionally, many bulimics go to great lengths to deceive friends and family -- hiding their symptoms for years. Some are successful, and may not get help until they reach their 30s or 40s.

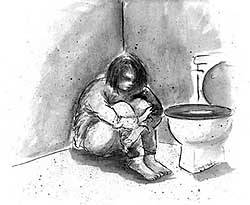

I vividly remember hiding my bingeing and purging behavior. After dinner, my parents would be busy doing the dishes, my brother would be reading or watching TV in the living room, and I would go into the bathroom to vomit. I'd close all the doors, blast my stereo in my room, and turn on the bathroom fan. Sometimes, fearing that I'd still be heard, I'd flush the toilet frequently to muffle the sounds of gagging and gasping for breath. Other times, I'd take a shower, vomit in the tub, and watch the water wash away the evidence of my weakness.

It was easier to hide the behavior itself than the effects on my body. My cheeks swelled; instead of looking thinner, I looked more like Marlon Brando in "The Godfather." Quite a few times, the strain of vomiting had burst blood vessels in my eyes. Facing myself in the mirror was hard enough, but constantly lying to my family and friends about my appearance and my behavior was even harder.

The effects from bulimia can range from minor problems -- like calluses on the hands from induced vomiting -- to death. Dental problems are very common; teeth become eroded and ruined by acid. Another common problem is enlarged salivary glands, which can become swollen from infection or irritation from the vomiting. Ruptures can also occur in blood vessels in the face, the stomach, or even in the esophagus. An esophageal rupture, which is fatal, can occur anytime you vomit -- whether it's the first time or the hundredth time you've purged.

The most serious side effect of purging is the damage it does to your organs. Diuretics can cause kidney dysfunction; laxatives may result in dependence or damage to the colon. Purging by laxative, diuretics, or vomiting can upset the body's balance of sodium, potassium, and other chemicals and cause dehydration. Upsetting or reducing the levels of these chemicals can cause heart rhythm disturbances or sudden death.

It is important to remember that an eating disorder is not just a problem, but an attempted solution to a problem. The eating disorder serves some purpose for the person. It may be that it is an effort to cope with stress or to communicate ideas and emotions. The person may have feelings of inadequacy, shame, or grief, which they may not be able to express openly. For whatever reason, a bulimic's life is too painful for her -- binging is her attempt to numb herself to the pain she feels. By counter-acting the binge, purging also releases her from pain and anxiety. A bulimic feels an inability to control her own life, and the bingeing and purging -- relieving pain by enjoying overeating followed by relieving the sense of guilt about the overeating gives the bulimic a false sense of control over her life. Whether she eats or doesn't eat, binges or purges, lives or dies -- it is her choice, even though the behavior by which she creates that feeling of control is itself out of control.

If you or someone you know is bulimic, there is help out there. Patients can be treated with medication, such as anti-depressants, to help with the depression and guilt. Most bulimics undergo psychotherapy to overcome the preoccupation with weight or body image and focus on the underlying issues of self-esteem and maladaptive thinking. Some patients receive exposure response treatments -- a bulimic patient eats anxiety-provoking food without vomiting, so that she or he can learn to eat without anxiety or guilt.

I can't imagine all the pain and suffering that Jennifer must have experienced. I know that my first few years with bulimia were a living hell -- I was destroying my body little by little. I'm thankful that I've made positive steps forward since then. I don't purge anymore, although I'm still preoccupied with my weight and body image. I try to accept myself for who I am, imperfections and all. It's a long, hard battle -- but one that I want to win. Being thin is not worth dying for.

Back to February/March '98 Issue