Donate to IMPACT

Click below for info

• Suing the U.S. Army

• Quickies

(music reviews)

• E-Mail Comments

• Archives

• Subscribe to IMPACT

• Where to Find

IMPACT

• Buy IMPACT T-Shirts

• Ordering Back Issues

• Home

|

An indignant, emotionally discountenanced parent of a former smoker walks out of a courtroom in Los Angeles to greet an audience of media personnel. He wears a proud smile, with wavering lips, and is caught between tears of joy and tears of anger.

On this day, a jury has passed judgment in his favor against big tobacco, proclaiming the company that produced the cigarettes used deceptive advertisement and irresponsibly withheld important information concerning factors of risk involved in participating in the act of smoking.

Jack's son Tom died as a result of a cancer that spread through his body until life escaped each of his pores. The allure of smoking--its social trappings, its flavor, its affect, its commercial appeal, its image as portrayed by decades of advertisement--lent Tom the motives to begin a hazardous career of smoking, which he ended in the glorious clutches of an IV and a hospital bed.

While the above story is but a fictitious illustration of the modern plight consumers and purveyors of tobacco face, the fact is, according to the Los Angeles Times, in Oregon alone "two cases filed by families of deceased smokers produced damage awards totaling $180 million." ("Ex-Smoker Wins Tobacco Suit", September 27, 2002)

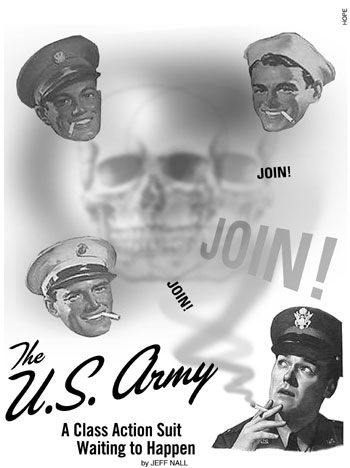

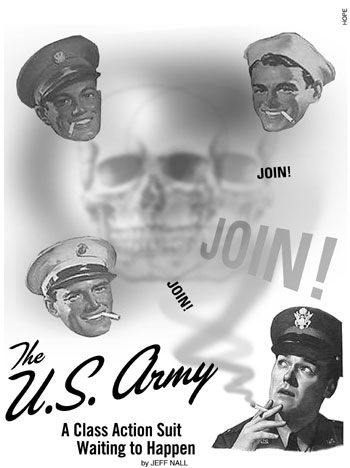

Now, I ask that those with a propensity to abstract thought replace the plaintiff with a family whose son or daughter has died in combat fighting a war in Iraq or protecting other foreign interests abroad. Furthermore, replace the defendant with the United States Army.

Seems like a stretch, you decide, responding aloud, "Soldiers willingly participate in joining the military. They also enjoy benefits, training and are paid very well."

But, I ask, is it really hard to fathom? One of the main reasons tobacco companies are forced to pay inordinate amounts of money to plaintiffs is because many courts have decided their former methods of advertisement and lack of warnings were adverse. Tobacco companies purposely omitted truths about the affects smoking could have on individuals; moreover they attempted to lure young impressionable people to a "pleasurable" activity via a potent ad campaign. Tobacco advertisements listed all the good and left the bad up to self-evident cognition.

"The military doesn't do that," many may remark. But upon closer examination, there appears to be some similarity between the two.

One of the best examples of such activity is found in the ranks of the Army. The new ad campaign--most have almost surely heard of--is themed "an Army of One."

Literature on this "Army of One" can be found at many high schools and on college campuses. In reading through the literature there is no mention of the perils that await those who enlist. Page after page speaks of the incentive to pay off college loans, receive medical and dental care and earn thousands of dollars each year. To many Americans this may sound like a dream come true. But if people are lured into a hazardous career in the military that may very well end in death, all because of a keen, misleading ad campaign, is the U.S. military--like big tobacco--liable for those deaths?

At one point, towards the end of one brochure found at a Central Florida community college, potential recruits are reminded of the opportunity to earn incentives totaling up to $85,000.

Another pamphlet reads: "Dear High School Graduate...Now it's time to make the rest of your dreams come true. The Air Force can help.

"We offer outstanding job and leadership training, a variety of programs to help you pay for college expenses, plus the free time you'll need to pursue your interests."

Another Air Force pamphlet reads, "Whether you are undecided how to go about achieving your goals or already have a plan, one thing's for sure: The Air Force Reserve will assist you in creating a life above and beyond."

Other than the seemingly paradoxical insinuation that one "creates" life by joining a military service, the literature goes on to list the following rewards for those who enroll: competitive pay; opportunity to travel; retirement program; leadership experience; camaraderie; and use of base facilities, including tax-free shopping privileges, golfing, bowling and more.

Meanwhile a Navy pamphlet lists that service's benefits as being "good pay, regular promotions when you qualify, opportunities for advanced education through the Montgomery GI Bill, Navy Tuition Assistance, and Navy College Programs, heath care and low-cost life insurance. All this and the opportunity to travel to places such as Italy, Spain, Hawaii, and Japan just to mention a few."

All this is said without the hint of the danger that awaits one who joins a group of working warriors. With bright literature, smiling faces on each page, donning a "why not join in the fun" demeanor, one can only wonder, why aren't we all in the Army? It not only pays for the education any free man deserves, it also pays you to go have fun in Hawaii.

This imagery draws comparison to beautiful women frolicking on the beach, who stop to take notice of an extra "cool" guy draining some nicotine down his pipes. That literature, in essence, is the image of a prototype of cool so many men attempt to achieve--that venerable rustic look of the Marlboro man. But like military literature leaving out images of dead bodies, we don't see the real Marlboro man suffering from cancer.

And although more solemn, the Marines pamphlet is laudatory as well, praying upon the adventure factor present in young adults. "There is a world out there that you have only heard about. It is a world where heroes are made and missions are accomplished." Still, there is no talk about the factor of death.

A bit unsettling, nearly each piece of literature speaks directly to high school students. "High school seniors can begin taking part in the Marine Reserve before graduation," reads one pamphlet. "You can work with your future reserve unit one weekend a month for up to twelve months, receiving four days pay for each weekend of service. Following graduation, you will go through recruit skills training to become a Marine Reservist."

John P. Boyce, Jr., public affairs specialist of the U.S. Army Public Affairs, Community Relations & Outreach Division in Washington, D.C., said the Army's literature does tell the real story of service. John P. Boyce, Jr., public affairs specialist of the U.S. Army Public Affairs, Community Relations & Outreach Division in Washington, D.C., said the Army's literature does tell the real story of service.

"Our literature, commercials and web information," he said, "show real recruits struggling with basic training, facing their personal challenges, working as team members and facing life's personal obstacles with the Army's values."

But when it comes to expressing the dangers of participating in the Army, Boyce feels there is nothing the Army can say about the perils people aren't already aware of.

"If they've ever seen a war movie, read a book about battle or seen a newscast about any war in the past 100 years, yes ... recruits are aware of the potential dangers as well as the benefits of fighting to defend our society."

When I asked Mr. Boyce to what extent recruiters discuss the dangers of being involved in the military, he said recruiters do not necessarily explain the horrors of war.

"Recruiters answer recruit's questions," said Boyce. "Recruits who do go on to military service also receive a healthy dose of military history, safety training and work in teams to anticipate and avoid most dangers. This is a vital part of our culture, along with our values."

Yet the question remains--is it too little too late? Should the military do more to warn impressionable recruits about the serious presence of danger and the potential death that awaits them? Do young recruits really understand that possibility?

College professor Sam Mason, an expert in psychopathology and psychology who is using an alias to protect his identity, says that young people up to 19 have not fully developed enough to understand the consequences of enrollment in the services.

"Prior to [military service], it doesn't exist, but once you're into the system then it becomes sort of a gung ho attitude," said Mason.

"There is no way to understand the whole grasp of [the dangers of potential service in war], it's too much first off. Developmentally their whole cognition is not even finished developing. You give a 17- or 18-year-old a gun, he might shake his head yes but I don't think he can fully understand the situation."

Mason also pointed out that in instances where people sign up for weekend service, many are caught off guard when actually called into full service.

"All these reservists that have been called up, one weekend a month, two weekends a year, did you ever think you'd be called up for war, [many are asking] what do you mean I have to go to war.' I believe a lot of people were shell shocked they had to go to war [during the Gulf War and now once more]."

Furthermore, Mason, who served in the military during Vietnam, explained his experience has adversely affected him in many ways he could not have imagined.

"It affected me, psychologically, emotionally, physically," he said. "It still affects me. You just can't push the button in the brain then erase it. The memories are there. I choose to live with it, but that's the cost I guess, and no one knows it before going into it."

In a country where most of the population--especially the poor--do not know what it's like to see a doctor on a regular basis or are used to earning minuscule wages offered at fast food restaurants, the benefits, in addition to the image of honor and prestige associated with serving one's country, are a barrage of pleasantries; only a fool would turn away from such a wonderful opportunity. And many, fearful of a struggling job market and a fruitless future filled with financial distress, choose to rely on the perennial economy of combat forces to provide living wages and prosperity. When the dangers of service are not addressed to the extent one would experience in getting one's driver's license (we've all seen the gory videos of fun nights on the town gone wrong) it leaves little wonder that service in the military is such a popular choice among our young people.

The more we inspect the issue, one distinct difference between tobacco companies and the armed forces becomes apparent--one comes with a warning of potential harm from the Surgeon General.

There is no warning at the bottom of an Army advertisement expressing "death by machine gun fire may occur," or "may cause psychological damage as we erase prior mode of behavior replacing it with license to kill."

Instead, we are shown Hollywood-produced commercials and glamorized literature that portrays a fun loving group of people getting paid to go to school, hang out together, and pursue their own interests.

In fact, it is known that the military spends at least 100 million dollars to produce these materials in an obvious effort to compel service, just as a company might encourage consumerism.

The military, too, is a business venture for many--American taxpayers spend more than 300 billion dollars each year on the industry that is the defense department. Though a public industry, many earn great annual salaries and the salaries of recruits expands as the number of recruits increases.

And just like smokers don't start smoking to enjoy its addictive properties or experience cancer as a result, recruits don't join the military to participate in combat. It's the image of smokers and valiant, impenetrable soldiers seen on TV that people are sold on. In an article written by Robert Hey, then-new recruit Shanan Burns is quoted as saying, "it sounds good to be a part of the world's greatest army." ("Military recruiters new message," The Christian Science Monitor, July 9, 2001) And just like smokers don't start smoking to enjoy its addictive properties or experience cancer as a result, recruits don't join the military to participate in combat. It's the image of smokers and valiant, impenetrable soldiers seen on TV that people are sold on. In an article written by Robert Hey, then-new recruit Shanan Burns is quoted as saying, "it sounds good to be a part of the world's greatest army." ("Military recruiters new message," The Christian Science Monitor, July 9, 2001)

For many, the Army sounds like a good idea, until they're actually deployed into open warfare. According to other professionals, many recruits are not seeking experience in combat or the ways of warriors, they're just trying to pad their resumé or pay off debts.

In the aforementioned article by Robert Hey, Norfolk, Va., Army recruiter Sgt. Marcus Campbell was quoted saying, "We've been seeing an influx of college-orientated applicants who want their college loans paid off, [or] who want money for college, who're looking to make themselves marketable."

While recruits seem to be guaranteed the best possible training from the greatest Army ever assembled, the question remains: do people know what they're getting into after reading literature and watching commercials that narrate, "If someone wrote a book about your life, would anyone want to read it," as one now on TV asks?

Mr. Boyce again reiterated that the U.S. military does, in fact, do all it can possibly do to ensure the health, training and safety of recruits after they've joined. He also said that the risks of service are well documented and known throughout the country. "As with firefighters, policemen and other professions, the risks of injury and death are well publicized in our society and well known throughout our nation's history. We address these legitimate fears by placing a high value on our soldiers' lives, being risk adverse to risking lives, planning precision military operations and, most importantly, training our people well," said Boyce.

So while it has become obvious to Americans that smoking harms the lungs, among other parts of the body, our justice department has held to the enlightened perspective that those peddlers of this product must accept responsibility for the manner in which they identify their product. Our juries and judges have scrutinized the methods by which advertisers achieve the goal of snatching up willing patrons and participants. Time and time again, these very institutions have questioned the professional ethics that tobacco CEO's continuously overlook, opting to concentrate on the benefits of smoking (e.g. the image, taste, positive affect) while avoiding the health risks until it was too late for so very many.

Whereas the tobacco companies are phasing out their use of billboards and advertising in sports stadiums, the U.S. Army has phased in sponsorship campaigns such as NASCAR stock cars and Arena League football jerseys. In the article mentioned earlier of the new message of the military, Brig. Gen. Duane Deal, commander of Air Force Recruiting Services, put it into perspective in saying, "We're on billboards. In Syracuse, New York we're even on milk cartons."

The new military image is a calculated attempt to encourage independent, thrill-seeking personalities to join a club that will pay for college, travel across the world, and an annual salary, not to mention free room and board. For many, this slanted campaign leaves much unsaid and allows silence to elucidate the most devastating of all physical disabilities, death.

Syndicated columnist Norman Solomon reviewed much of the "army of one's" recruitment materials. ("Media Sizzle for an Army of Fun" August/September 2002, IMPACT press) He explains that simply by calling the Army's 800 number, one can receive a free Army T-shirt and a video called "212 Ways to be a Soldier." The article describes the video as "graphics flash with a cutting edge look (supplied by a designer who gained ad-biz acclaim for working on a smash Nike commercial)."

The article adds, "There's no talk of risk and scarcely a mention of killing." The military would seem to be serving impressionable thrill seekers loads of fun without the danger.

In the video, soldiers hail the promise of college education and exciting careers as important benefits, according to Solomon. The U.S. military has even released a video game, once again putting a fantasy spin on the realities of training for and fighting wars.

Like any corporation, the military seems to have set its sights on growing. Organizations like the ROTC at high schools and colleges are not uncommon and are expanding. Recruiters are now even given access to public high school students without the permission of parents, so that they may pursue individuals thought to be good candidates for service.

But the question is not whether the military is good or bad, necessary or superfluous. The question is, are they liable for the deaths of those tantalized by a glorious, seemingly fun environment in the armed forces? Should parents, wives and children have the right to sue the Army for the loss of their loved ones?

Mr. Boyce believes the Army is responsible for those soldiers that serve the institution. He says they have done and continue to do their best to ensure the well being of their personnel.

"The Armed Forces protect their people," he said, "mitigate risks, provide rigorous, realistic training and serve at the direction of the president and the American people. Our government, in fact, does assist with soldiers group life insurance, casualty assistance and family benefits ... but we work far harder to avoid deaths. So, yes, our government and our society is liable in many profound aspects for the deaths of military personnel ... and has been for 227 years. America honors those brave souls each Memorial Day and recognizes the living each Veterans Day."

But the question remains--would 70 million Americans be enrolled in the service if they believed their lives were at risk? Would they think twice before joining if advertising were forced to include an explicit warning that soldiers may die, and show the number of military casualties including deaths, and resulting cases of debilitation and mental-illness? Because, while it's obvious cigarettes cause cancer, one must ask if the intent of advertising weren't coercive, why would companies spend millions to make the perfect commercial? Why would the U.S. military? And if people were so interested in being a soldier, why is it necessary to spend so much time, effort and money engaging them?

The mediums in use seem to be specifically designed to garner the interests of a young video game playing, thrill-seeking generation. Simply put, advertising sells products. Or does it simply inform?

Mr. Boyce said the military's goal is to use the means at its disposal and let Americans know what the Army today is about.

"Our goal is to show people what it's like to be in the Army today using many different media to meet their information needs and desires. It's also reinforced and clarified by talking with people who've made the choice to serve our nation freely."

Still, one must consider that most Americans know cigarettes are bad for them and can cause death. Yet tobacco companies are forced to label their products as harmful and are not allowed to advertise anywhere near schools where children attend. So while Americans may very well recall the deaths of Vietnam, it might take a reminder, a warning label on the beautifully packaged career in the military, to enlighten recruits (especially those who weren't around to endure a fiasco like Vietnam) of the horrors TV and books can never properly depict.

Each American deserves the right and privilege to serve our great nation, but each should also be fully aware of the perils that can hardly be imagined, should one engage the enemy in open warfare. One should be told of the apocalyptic nature of war, where each second survived is but a fleeting blessing from a hell unimaginable. Just take a look at the photojournalists who documented the last Gulf War, the charred bodies of civilians and soldiers, who once were civilians like many of our young people, and who just happened to be wearing fatigues in hopes of bettering their lives and the lives of their families.

•

Email your feedback on this article to editor@impactpress.com.

|

And just like smokers don't start smoking to enjoy its addictive properties or experience cancer as a result, recruits don't join the military to participate in combat. It's the image of smokers and valiant, impenetrable soldiers seen on TV that people are sold on. In an article written by Robert Hey, then-new recruit Shanan Burns is quoted as saying, "it sounds good to be a part of the world's greatest army." ("Military recruiters new message," The Christian Science Monitor, July 9, 2001)

And just like smokers don't start smoking to enjoy its addictive properties or experience cancer as a result, recruits don't join the military to participate in combat. It's the image of smokers and valiant, impenetrable soldiers seen on TV that people are sold on. In an article written by Robert Hey, then-new recruit Shanan Burns is quoted as saying, "it sounds good to be a part of the world's greatest army." ("Military recruiters new message," The Christian Science Monitor, July 9, 2001)