Donate to IMPACT

Click below for info

• Global Fear & Loathing

• Quickies

(music reviews)

• E-Mail Comments

• Archives

• Subscribe to IMPACT

• Where to Find

IMPACT

• Buy IMPACT T-Shirts

• Ordering Back Issues

• Home

|

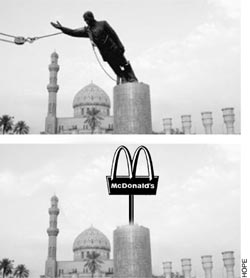

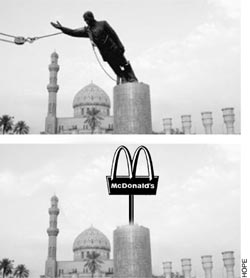

art/Tom Hope

IN AN ADDRESS AT WRIGHT-PATTERSON AIR FORCE BASE in Dayton, Ohio on July 4, President George W. Bush proclaimed, "Today all who live in tyranny and all who yearn for freedom place their hopes in the United States of America." Bush's audience cheered enthusiastically–and not just because any protest by active-duty military personnel might have been punished. After all, the representation of America as the world's foremost guardian of freedom has been a staple of bourgeois ideology for two centuries. As Bertrand Russell once said, "It is in the nature of imperialism that citizens of the imperial power are always among the last to know–or care–about circumstances in the colonies."

But in the aftermath of the horrific September 11th attacks, the subsequent invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and Bush's declaration of an endless "War on Terror," all of us need to face the facts about the U.S.government's role in the world and how people in other countries see us. As Pakistani journalist Mushahid Hussain has pointed out, "Their deeply ingrained empathy, candor, humor, and hard work endear Americans to all those who interact with them." ("'Anti-Americanism' Has Roots in U.S. Foreign Policy," October 19, 2001, Inter Press Service.) Nonetheless, it is time to recognize that many people across the planet consider the U.S. government an enemy of freedom and view Washington with fear and loathing.

The depiction of America as "the land of the free" has some limited grounding in history. In early America, some colonists found freedom from religious persecution and old-style European aristocracy. The desire for freedom from British "taxation without representation" led to revolution and independence. The framers of the Constitution rejected monarchy in favor of a republican form of government. And over the next two centuries, collective political action by workers, women, and people of color brought about significant progress. It seems safe to say that freedom has been an aspiration or ideal for many Americans for more than 200 years.

But people throughout the world have long criticized the savage exploitation of labor, the ruthless conquest of other peoples' lands and resources, the support for foreign tyrants, and other human costs associated with the rise of the American Empire. Frederick Douglass exposed America's most glaring contradictions in an Independence Day address in 1852:

But people throughout the world have long criticized the savage exploitation of labor, the ruthless conquest of other peoples' lands and resources, the support for foreign tyrants, and other human costs associated with the rise of the American Empire. Frederick Douglass exposed America's most glaring contradictions in an Independence Day address in 1852:

"What to the American slave is your Fourth of July? I answer, a day that reveals to him...the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty an unholy license...For revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival."

When the Spanish colonies of Latin America fought for their independence, the U.S. government refused to help them because it wanted to maintain good relations with Spain, because the insurgents opposed slavery, and because many of the insurgents themselves were of mixed ancestry. Moreover, the Monroe Doctrine made clear that the U.S. would henceforth regard the Western Hemisphere as its sphere of influence. As Simon Bolivar later remarked, "The United States seems destined by Providence to spread misery in the name of liberty." Certainly, U.S. expansionism in the era of "Manifest Destiny" confirmed Bolivar's fear. By 1848, the U.S.had taken half the territory of Mexico by force.

During the 19th century, the U.S. government rationalized its extermination or forced relocation of indigenous peoples in terms of "the progress of civilization." But as historian Howard Zinn has pointed out, the human lives lost and suffering incurred in this process will never be adequately measured. In 1811, Shawnee Chief Tecumseh told his warriors, "Let the white race perish! They seize your land; they corrupt your women; they trample on the ashes of your dead! Back whence they cameŠthey must be driven." But by 1854, Suquamish Chief Seattle recognized the terrible truth: "Our people are ebbing away like a rapidly receding tide that will never return...It matters little where we pass the remnant of our days. They will not be many."

In the decades ahead, the U.S. used or threatened violence against various nations in order to advance capitalist interests. But the peoples oppressed by the American Empire turned out to have very long historical memories. Even today, popular resentment of "gunboat diplomacy" in Caribbean and Latin American countries remains prevalent. Even today, the native people of Hawaii continue the struggle to reclaim their national sovereignty. Even today, the knowledge that troops from the Sixth U.S. Cavalry occupied Beijing in 1900-1901 nourishes anti-American sentiments in China. Reinhold Niebuhr warned in the early 1930s, as the U.S. had become a new kind of empire, "it is inevitable that men should hate those who hold power over them."

During most of the 20th century, U.S. officials claimed that our foreign policy was based on defending freedom and democracy against the threat of communist dictatorship. In truth, Washington was primarily concerned with defending capitalist regimes–no matter how bloodthirsty or brutal–and suppressing popular, democratic, and radical movements against such regimes. U.S. participation in the anti-Communist invasion of Russia in 1918, close U.S. business ties with Nazi Germany and Fascist Japan during the 1930s, the totally unnecessary atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, and the use of violence and subversion to thwart postwar leftist victories in Greece, Italy, France and Japan all helped fuel global opposition to U.S. imperialism. During most of the 20th century, U.S. officials claimed that our foreign policy was based on defending freedom and democracy against the threat of communist dictatorship. In truth, Washington was primarily concerned with defending capitalist regimes–no matter how bloodthirsty or brutal–and suppressing popular, democratic, and radical movements against such regimes. U.S. participation in the anti-Communist invasion of Russia in 1918, close U.S. business ties with Nazi Germany and Fascist Japan during the 1930s, the totally unnecessary atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, and the use of violence and subversion to thwart postwar leftist victories in Greece, Italy, France and Japan all helped fuel global opposition to U.S. imperialism.

Although the limits of Soviet-style socialism became clear enough, the United States was much more widely reviled and dreaded in the years after the Second World War. After forcing the partition of Korea and installing a right-wing dictator in the southern part of the country, the U.S. fought a war to preserve its little protectorate in the early 1950s–and four million people died as a result. Under similar circumstances, the U.S. waged another war in Vietnam in the 1960s and early 1970s–and another four million people died. In 1965-1967, the U.S. government gave the green light to the Indonesian Army to arrest and execute 1 million people suspected of being radicals.

Many people have died at the hands of U.S. invaders in Lebanon, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Grenada, Panama, Libya, Somalia and other Third World countries. And many more have died at the hands of dictators and death squads supported by Washington–in Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador, Argentina, Chile, Iran, the Congo, the Philippines and elsewhere. Before his arrest and imprisonment by the U.S.-supported apartheid regime in South Africa, Nelson Mandela warned that "American imperialism... must be fought and decisively beaten down." Before his capture and execution by U.S.-trained troops in Bolivia, Che Guevara concluded that the U.S. government had become "the great enemy of mankind."

Since the 1990s, U.S. government officials and business owners have portrayed the collapse of the Soviet Union as irrefutable proof of the superiority and inevitability of capitalism. In this historical context, it is both ironic and enlightening that militant anti-imperialists like Nelson Mandela and Che Guevara continue to be among the most widely revered heroes on the planet. Part of the explanation for this has been provided by the famous Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano, who has remarked, "For us, capitalism is not a dream to be made reality, but a nightmare come true." Certainly, the 1990s witnessed the persistence and exacerbation of this "nightmare" for much of the world's population.

In 1991, the first Bush Administration used Saddam Hussein's attack on Kuwait as a pretext for killing 200,000 Iraqis, stationing U.S. troops near the holiest Islamic sites in Saudi Arabia, and increasing aid to Israel. In the decade that followed, U.S.-enforced economic sanctions killed more than one million Iraqis and U.S. bombs killed thousands of Yugoslavs. But as the new millennium dawned, widespread opposition to U.S. militarism and corporate-led "globalization" was becoming difficult to ignore, even in the heart of the Empire.

In the aftermath of the September 11th attacks, many Americans sought to understand how any foreign enemy could inflict such an awful blow against innocent civilians in our country. Countless journalists and professors posed the same question: Why do they hate us so much? Unfortunately, the mainstream media and the academic establishment rushed to embrace Bush's Big Lie that the U.S. had been attacked because we are "a beacon of freedom and democracy." To this day, most Americans still do not know what many people in other countries know–that the heinous attacks by al-Qa'ida might be described as the terror that terror produced.

However, an opinion survey of political, business, and media leaders in 24 nations in the following months revealed some interesting things about the way the world views the U.S. Although the poll found substantial sympathy for the American people's grievous losses, it also found that, "Opinion leaders in most regions say U.S. policies are believed to be a principal cause of the Sept. 11 attack." Strikingly, respondents in every part of the world agreed, "It is good that Americans now know what it is like to be vulnerable." ("America Admired, Yet Its New Vulnerability Seen As Good Thing, Say Opinion Leaders," Pew Research Center, December 19, 2001.)

In many nations, sympathy turned to disgust when the U.S. killed thousands of Afghan people in the process of overthrowing the Taliban, installing a friendly client regime, and securing agreements for oil and gas pipelines through the country. Within a year, the largest global anti-war movement in history had developed as people from Sao Paulo to Seoul marched and rallied against the impending U.S. invasion of Iraq. Throughout most of the world, disgust turned to outrage when the Bush Administration killed thousands of Iraqi people in the process of ousting Saddam Hussein, installing another friendly client regime, and seizing control of the Iraqi oil fields.

More than a few internationally acclaimed critics have warned about the growing dangers posed by the American Empire. The Indian author Arundhati Roy has pointed out that Bush's ultimatum to the world–"If you're not with us, you're against us"–is "a piece of presumptuous arrogance. It's not a choice that people want to, need to, or should have to make." British playwright Harold Pinter has said, "The American Administration is now a bloodthirsty wild animal." And Nelson Mandela recently told an audience in Ireland that Bush and the U.S. government "are a danger to the world."

Indeed, world opinion today regarding America's role in the world may be at a historic low point. A 2002 Pew Research Center (PRC) survey of more than 38,000 people in 44 countries found, "Discontent with the United States has grown around the world over the past two years. Images of the U.S. have been tarnished in all types of nations: among longtime NATO allies, in developing countries, in Eastern Europe and, most dramatically, in Muslim nations" ("What the World Thinks in 2002," December 4, 2002).

A later PRC survey of more than 16,000 persons in twenty countries found, "In most countries, opinions of the U.S. are markedly lower than they were a year ago. The war [on Iraq] has widened the rift between Americans and Western Europeans, further inflamed the Muslim world, softened support for the war on terrorism, and significantly weakened global public support for...the UN and the North Atlantic alliance." ("Views of a Changing World 2003," June 2003.). A later PRC survey of more than 16,000 persons in twenty countries found, "In most countries, opinions of the U.S. are markedly lower than they were a year ago. The war [on Iraq] has widened the rift between Americans and Western Europeans, further inflamed the Muslim world, softened support for the war on terrorism, and significantly weakened global public support for...the UN and the North Atlantic alliance." ("Views of a Changing World 2003," June 2003.).

As PRC Director Andrew Kohut has noted, the latest survey results show, "The bottom has fallen out" in Muslim countries. "Very unfavorable" or "somewhat unfavorable" views of the U.S. were expressed this spring by 99 percent of the respondents in Jordan, 98 percent in Palestine, 83 percent in Turkey, 83 percent in Indonesia, 81 percent in Pakistan, 71 percent in Lebanon, and 66 percent in Morocco. As Kohut concluded, "Anti-Americanism has deepened, but it has also widened...People see America as a real threat. They think we're going to invade them."

Global fear and loathing concerning the American Empire has also taken root in countries which have historically been close allies. In the May 2003 PRC survey, "very unfavorable" or "somewhat unfavorable" views of the U.S.were expressed by 57 percent of the respondents in France, 56 percent in Spain, 54 percent in Germany, and 50 percent in South Korea. As Glenn Frankel reported in The Washington Post article "Anti-Americanism Moves to Europe's Political Mainstream" on February 11, 2003, "Anti-Americanism, West-European style, is wide-spread [and] risingŠThe immediate focus might be U.S. policy toward Iraq, but the larger emerging theme is an abiding sense of fear and loathing of American power, policies, and motives."

Other recent international polls confirm the growing negative perception of the United States. A Gallup International Association survey of public opinion in 45 countries, released in May 2003, documented massive global opposition to the U.S. invasion of Iraq. This survey also found that, in more than two-thirds of the countries, more people thought U.S. foreign policy had a negative effect on their nation. In addition, the survey found that, apart from Albania, Kosovo, and the U.S. itself, "Majorities in all other countries think that as a result of recent military action in Afghanistan and Iraq, the world is a more dangerous place." ("Press Release: New Gallup International Poll," May 13, 2003.).

A British Broadcasting Corporation survey of public opinion in 11 countries, released in June 2003, was hardly more flattering to the U.S. Sixty-five percent of all respondents described the U.S. as "arrogant," and 60 percent expressed a "very unfavorable" or "fairly unfavorable" view of President Bush. The majority of respondents expressed the view that the U.S. is a greater threat to world peace than Iran or North Korea. Remarkably, even in South Korea, 48 percent of the respondents stated that the U.S. is a greater threat than North Korea. ("Poll Suggests World Hostile to U.S.," June 16, 2003.)

The people of the United States should be deeply concerned about the growing fear and loathing our government is fostering around the world. Notwithstanding the mixed history of our country, millions of Americans genuinely support the expansion of freedom and democracy–not exploitation and empire–at home and abroad.Many of us also realize that the persistence of U.S. imperialism precludes the genuine international solidarity and cooperation, which is needed to uproot transnational problems like poverty, pollution, racism and terrorism.

Moreover, if the U.S. power elite continues to subjugate and pillage the planet, our country will undoubtedly suffer new, possibly catastrophic terrorist attacks in the coming years. The prospect of aggrieved foreign groups unleashing chemical or biological agents against major population centers is no longer inconceivable. Such attacks might lead not only to the grievous oss of life, but also new kinds of "national security" measures, which could further erode our already precarious rights and liberties. From this perspective, collective political action to begin to dismantle the American Empire is not quixotic or utopian, but imperative for our survival.

•

Dr. David Michael Smith is a professor of government at the College of the Mainland in Texas City, Texas. His e-mail is Dsmith@com.edu

Email your feedback on this article to editor@impactpress.com.

Other articles by Dr. David Michael Smith:

|

But people throughout the world have long criticized the savage exploitation of labor, the ruthless conquest of other peoples' lands and resources, the support for foreign tyrants, and other human costs associated with the rise of the American Empire. Frederick Douglass exposed America's most glaring contradictions in an Independence Day address in 1852:

But people throughout the world have long criticized the savage exploitation of labor, the ruthless conquest of other peoples' lands and resources, the support for foreign tyrants, and other human costs associated with the rise of the American Empire. Frederick Douglass exposed America's most glaring contradictions in an Independence Day address in 1852: During most of the 20th century, U.S. officials claimed that our foreign policy was based on defending freedom and democracy against the threat of communist dictatorship. In truth, Washington was primarily concerned with defending capitalist regimes–no matter how bloodthirsty or brutal–and suppressing popular, democratic, and radical movements against such regimes. U.S. participation in the anti-Communist invasion of Russia in 1918, close U.S. business ties with Nazi Germany and Fascist Japan during the 1930s, the totally unnecessary atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, and the use of violence and subversion to thwart postwar leftist victories in Greece, Italy, France and Japan all helped fuel global opposition to U.S. imperialism.

During most of the 20th century, U.S. officials claimed that our foreign policy was based on defending freedom and democracy against the threat of communist dictatorship. In truth, Washington was primarily concerned with defending capitalist regimes–no matter how bloodthirsty or brutal–and suppressing popular, democratic, and radical movements against such regimes. U.S. participation in the anti-Communist invasion of Russia in 1918, close U.S. business ties with Nazi Germany and Fascist Japan during the 1930s, the totally unnecessary atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, and the use of violence and subversion to thwart postwar leftist victories in Greece, Italy, France and Japan all helped fuel global opposition to U.S. imperialism.

A later PRC survey of more than 16,000 persons in twenty countries found, "In most countries, opinions of the U.S. are markedly lower than they were a year ago. The war [on Iraq] has widened the rift between Americans and Western Europeans, further inflamed the Muslim world, softened support for the war on terrorism, and significantly weakened global public support for...the UN and the North Atlantic alliance." ("Views of a Changing World 2003," June 2003.).

A later PRC survey of more than 16,000 persons in twenty countries found, "In most countries, opinions of the U.S. are markedly lower than they were a year ago. The war [on Iraq] has widened the rift between Americans and Western Europeans, further inflamed the Muslim world, softened support for the war on terrorism, and significantly weakened global public support for...the UN and the North Atlantic alliance." ("Views of a Changing World 2003," June 2003.).