IMPACT

press

Oct.-Nov. '00 Articles:

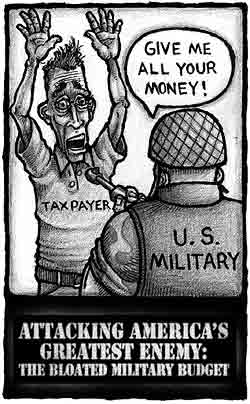

America's Greatest Enemy: The Bloated Military Budget

E-Mail Us

Your Comments

|

by Craig Butler

art/Eric Spitler

"Every gun that is made, every warship that is launched, every rocket fired signifies in the final sense a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and not clothed."

A quick quiz to start us off. Which of the following commie-radical-hippie-peaceniks is responsible for the above quote about the dangers of a bloated military: Bill Clinton, Ralph Nader, or Dwight Eisenhower?

Although Nader is certainly committed to the idea expressed in the quote, and though Clinton would claim to be, the words themselves come from no one but Ike. He even went on to say that when money is wasted on unneeded military expenses, the world is sacrificing more than money, "it is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists and the hopes of its children."

Of course, most Americans agree that they want a strong military. But most Americans don't realize just how much money we spend on our military - or just what we get for that money.

When Bill Clinton presented his budget for fiscal year (FY) 2001, he earmarked some $305 billion for defense, roughly $836 million per day. Total discretionary spending in Clinton's budget is $622 billion -- which means that the military accounts for 49% of next year's discretionary spending as proposed by the President. (Discretionary spending is that portion of the budget that is voted on annually, as opposed to Social Security, debt payments, Medicare, etc.) By contrast, Clinton proposed $42 billion for education (6.8% of discretionary funds), $35 billion for health (5.6%), and $15 billion for transportation (2.4%).

These numbers, by the way, don't tell the whole story. These figures will undoubtedly be changed by the time the House and Senate get finished with them. For example, the President's budget includes a 36% increase in education and a 59% increase in housing, increases which will likely be trimmed, if not severely cut.

Nor will the military budget remain intact, although the GOP-lead Congress will want to INCREASE spending beyond the $305 billion Clinton has proposed. They have already added over $3.6 billion to the Defense appropriations bill, most (if not all) of which is "pork," or money spent on items which the Pentagon doesn't want, doesn't need and didn't request. (More on that later.)

So we spend a hell of a lot of money on defense. Doesn't everyone?

Well, actually, no. No other country spends money on their military like we do. No one even comes close. Russia, with the second-largest military budget, will lay out roughly $55 billion for defense next year - about 18% of what we will spend. As a matter of fact, our military budget is larger than the combined military budgets of the next twelve nations. And none of those next twelve nations listed are one of the seven "rogue nations" (or "states of concern," as they've recently been rechristened) that are considered enemies of the U.S. (Our defense budget, by the way, is twenty-two times the combined amount of money those seven nations will spend. It is more than 50 times greater than Iran's, which has the largest budget of the seven.)

Defenders of the military budget, paradoxically enough, claim that we spend too LITTLE on defense. They claim that under Clinton the budget has been slashed drastically; that our "readiness" has declined substantially; that our forces are weak because we don't pay our soldiers enough; and that we must constantly be purchasing new equipment because the current equipment is old and obsolete.

It is true that Clinton has reduced the military budget, but the reduction is "drastic" only in comparison with the excesses of the Reagan era when the military budget ballooned out of control (causing the National Debt crisis and changing the U.S. from the world's largest creditor nation to the world's largest debtor.) And in fact, Clinton's budget is still 90% of what we averaged over the life of the Cold War (in real dollars) - despite the fact that the Cold War justification for such huge expenditures no longer exists.

The "readiness" argument also does not hold water and is based upon a belief that we spend too little on O&M (operations and maintenance). In fact, there is no reason to assume that readiness rates are related to spending. Under Reagan, they dropped between 1980 and 1984, despite the increased monetary support they received. But even if there is a relation, on a per capita basis, we are spending 10% more than we did at the height of the 1980s build-up.

As far as the issue of pay goes, an entering recruit with only a high school diploma earns $22,000 per year currently, plus such benefits as free health care, which beats what you'd get folding trousers at GapKids. Career officers often pull down salaries over $100,000. And the FY 2000 and 2001 budgets contain a 9% across-the-board base pay increase. More importantly, while politicians like to claim that increased military budgets are necessary to provide better compensation for enlistees, the vast majority of such increases go to procuring, maintaining or improving weapons and equipment.

What about old and obsolete equipment? Well, of course there are instances where a piece of equipment has served its purpose and must be replaced. More often, however, simple maintenance or upgrading is all that is required rather than replacement. Think of it this way: If you have a personal computer that works just fine and has many years of life left in it, do you chuck it out the window and buy a whole new system just because a new version of Windows comes on the market?

So our military budget is too big. What's an appropriate size? That's a question that is certainly open to debate. Business Leaders for Sensible Priorities (BLSP), an organization which has devoted a lot of time and money to considering this question, believes that $40 billion could be safely cut right away. Lawrence Korb, a former Assistant Secretary of Defense in the Reagan administration, believes that a $225 billion military budget - $80 billion less than the current budget - would be sufficient. Bill Hartung of the World Policy Institute, believes that the budget could be reduced by up to $100 billion per annum.

Jack Shanahan, a retired Admiral who heads BLSP's Military Advisory Council, notes that almost half of the proposed $40 billion cut could come merely from reducing our stockpile of nuclear weapons from 12,000 - enough to destroy every major city in the world twelve times over - to "a still insane level of 1,000." Korb details very specific cuts which would still leave us with a force of 2 million men and women. And Hartung makes the case that taking into consideration our real needs in the context of the real world (e.g., the current and potential contributions of our allies, a policy of conflict prevention, the viability of the "two war" strategy, etc.) would enable us to trim the budget as needed without endangering security.

The viability of the "two war" strategy is key to remaking our military budget. Essentially, this strategy states that the United States must be ready to fight two full-scale wars at any one time. But

"the two wars argument is a Trojan Horse," states Maurice Paprin, Co-Chair of the Fund for New Priorities in America. "It's an attempt to pull the wool over the public's eyes. We have never encountered such a situation before in the history of our country. Look at the last fifty years. Korea didn't overlap with Vietnam, and Vietnam didn't overlap with the Persian Gulf. But without the two wars scenario, there is no way for the Pentagon to justify its obscene budgets."

Paprin's argument is supported by Merrill McPeak, Air Force Chief of Staff during the Persian Gulf War, who says that the "two war strategy is just a marketing device to justify a high budget." Even Colin Powell, who created the strategy, acknowledged at the time that he was "running out of enemies." Korb counters that, even if the two war strategy is accepted, the budget he proposes would provide every bit as much combat capability as the two war strategy demands. "Besides," Paprin adds, "the Pentagon is essentially assuming that the United States would be fighting this war single-handedly, whereas a more realistic assumption is that we would be part of a multi-national effort" in any conflict in which we become engaged.

Paprin's argument is supported by Merrill McPeak, Air Force Chief of Staff during the Persian Gulf War, who says that the "two war strategy is just a marketing device to justify a high budget." Even Colin Powell, who created the strategy, acknowledged at the time that he was "running out of enemies." Korb counters that, even if the two war strategy is accepted, the budget he proposes would provide every bit as much combat capability as the two war strategy demands. "Besides," Paprin adds, "the Pentagon is essentially assuming that the United States would be fighting this war single-handedly, whereas a more realistic assumption is that we would be part of a multi-national effort" in any conflict in which we become engaged.

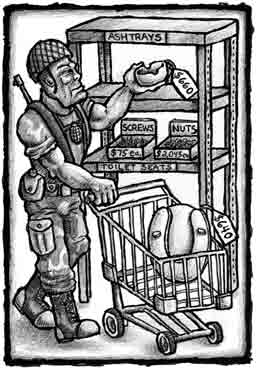

Interestingly, there's reason to believe that the budget could be reduced significantly if only the Pentagon were held to the same standards of efficiency that apply to the rest of the country. For example, over a 10-year period (1987-1997), the Pentagon spent $43 billion that it claims it simply cannot account for. It overstocked $41 billion worth of equipment, such as a quantity of camouflage screen systems sufficient to last 159 years - even though they are scheduled for replacement in 2003. And, as BLSP points out, it routinely makes such overpayments as $640 for a toilet seat, $75 for a 57-cent screw, $2,043 for a nut, $660 for an ashtray, and $1,118 for "a plastic cap that goes over the end of a stool leg."

And then there's "pork," which as I indicated earlier is money that the Senate and Congress throw at the Pentagon for things it doesn't want, doesn't need and didn't request. So why do they do this? Simple - because the money goes to the individual Senator or Representative's home district. That's why since 1978 Congress has purchased 256 C-130 transport planes (cost in 1999: about $80 million per plane), despite the fact that the military asked for only five. Those planes are built and/or maintained in the home states of Senate Majority leader Trent Lott and former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich. (Pork is not limited to Republicans, of course. For example, Senator Daniel Inouye's home state of Hawaii benefitted from unwanted add-ons to 1999's military budget to the tune of $258 million.)

Of course, there's another reason politicians are forever increasing the military budget - the military contractors, who are extremely generous in making campaign donations to those elected officials who feed them such lucrative deals.

From 1991 to 1997, defense companies contributed $32.3 million to candidates and parties (as compared to the tobacco industry's $26.9 million during the same period).

A 1999 report also found that over a two-year period the six top defense contractors spent $51 million on lobbying activities, unrelated to direct political donations. Increasingly in contemporary America, money equals power. More and more this results in our military strategy being determined not by what is best for the country's defense but by what is best for military contractors' pocketbooks.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the current push to create a National Missile Defense (NMD) system. Reagan first advanced this idea with his Strategic Defense Initiative, often referred to at the time as "Star Wars." Although it was shot down in the 1980's, it has refused to die, with Congress still providing annual funding for the development of a missile defense program to protect us from strikes by other countries. The current version, NMD or "Son of Star Wars," has absolutely nothing going for it from a defense point-of-view.

The basic premise behind NMD is that we would install a huge number of missiles at strategic points around the world, creating a missile shield which would detect any hostile missiles coming our way and knock them out of the sky almost immediately. This is a difficult thing to do, basically the equivalent of trying to stop a bullet by firing another bullet at it. Not surprisingly, NMD has failed its preliminary tests, proving itself unable to differentiate between a mock warhead and a balloon - this despite the tests being performed in optimum controlled conditions which would never be recreated in the real world.

Opponents to NMD also point out that even if it worked, the system still should not be approved. The last land-based missile defense system the U.S. tried, the $29 billion Safeguard, was declared obsolete 145 days after it had been put into operation. In addition, the NMD is a violation of existing and pending treaties, a fact which angers and concerns the international community and could result in the destablization of important relationships. And finally, "advances" such as NMD inevitably lead to an expensive and dangerous arms race (which also hastens the system's obsolescence.)

Leading scientists and respected military veterans have criticized NMD, and some members of Congress, such as Dennis Kucinich and Barney Frank, have also expressed doubts about it. Yet the overriding question as far as Washington is concerned is not whether we should have an NMD, but how big it should be, with Clinton proposing a $60 billion version and the Republican leadership countering that a $240 billion version is necessary. And why? Because the generous folk at Lockheed Martin, Boeing and Raytheon have made clear how much an NMD would mean to them.

The fact that the U.S. spends too much on its military is alone sufficient justification for demanding that the budget be cut back. But there are other reasons as well. There is, for example, the moral argument that we as a civilized nation should be seeking pathways to peace rather than continuing on a road to war. There is also the belief that the U.S. should get out of the role of "Globo-Cop" and stop trying to be the police force to the world.

And there is the matter of "opportunity costs." Basically, this argument stresses that money which is spent on the military is money which is NOT being spent elsewhere (or, in some views, money which is being TAKEN from another program.) And these opportunity costs are substantial.

Suppose, for example, that we succeeded in cutting the military budget by $40 billion. Figures compiled by BLSP show that money thereby saved could then be used for the following:

- providing health care for every uninsured child in America ($6 billion)

- fully funding Head Start programs for all eligible children ($8 billion)

- paying for two years of meals for hungry seniors ($17 billion)

- providing housing for 500,000 homeless families ($3 billion)

- building 1,000 new elementary schools ($6 billion)

These are just samples, of course. You can plug in your own priorities. Child care for 1.1 million low income families ($6 billion)? Juvenile crime prevention for 1.5 million youths ($5 billion)? Middle class tax cut ($10 billion)?

And spending money on programs like those listed above rather than on defense would have another benefit: job creation. Although the defense industry contractors like to point to the large number of employees they have, a study by the National Priorities Project (NPP) shows that they are not as good at generating jobs as they would have us believe. According to NPP, if we invest $1 billion in military procurement, approximately 25,000 jobs are created. But that same $1 billion invested in mass transit yields 36,000 jobs. Put it into education or healthcare and you create 41,000 and 47,000 jobs, respectively.

The point is this: America has fallen into a trap of pouring money into a military budget in such a way that our realistic defense needs are not met and resulting in a scandalous waste of money and resources. Rather than continuing on this path, we must cut the unhealthy fat out of the military and redirect our priorities to domestic programs that need the money and actually benefit the public.

Our elected leaders and the Pentagon, happy with the status quo and supported by the deep pockets of the defense industry, are not going to take action themselves. The only way we can bring this about is through building a critical mass - through letters, town hall meetings, phone calls, demonstrations, etc. - that demands change.

•

Make an IMPACT

Email your feedback on this article to editor@impactpress.com.

Other articles by Craig Butler:

|