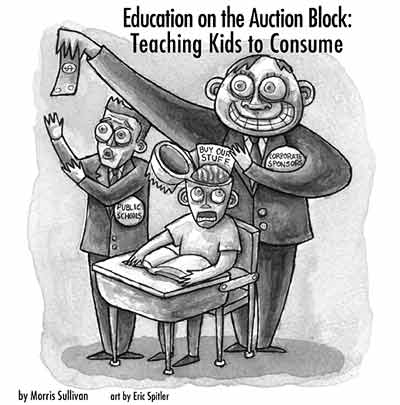

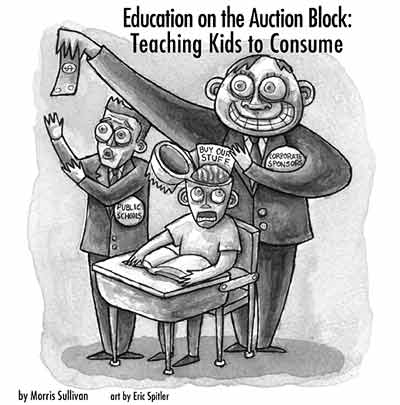

Education?: Teaching Kids to Consume

E-Mail Us

Your Comments

|

by Morris Sullivan

art/Eric Spitler

It's back-to-school time--time to hit the books and learn new things: how to factor an equation, for example; and that the capital of Idaho is Boise; that America entered World War II after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor; that "antidisestablishmentarianism" is a noun; and that Pepsi is better than Coke.

Schools have displayed and disseminated corporate propaganda for a long time. In the '60s, some accepted free book covers, printed with ads, for example. Coke and Pepsi have long been out-bidding each other for the right to advertise on stadium scoreboards, and everything from band candy to book fairs turned school kids into marketing devices, pushing products to help fund school activities.

From time to time, the practice of using American schoolchildren to help turn a profit has stirred up controversy; even as early as 1929, enough concern existed about corporate influence over curriculum to prompt the National Education Association to create a Committee on Propaganda in the Schools.

In recent decades, school budget crunches have driven many school districts to look for creative ways to fund their needs, and corporations have been quick to respond with dazzling deal-making. America's kids are a large and growing market; pre-teen children spend about $15 billion per year and influence their parents to spend another $160 billion; teenagers spend about $57 billion of their own allowance and talk mom and dad into spending another $36 billion. The situation was summed up in a 1995 interview with James U. McNeal, president of McNeal & Kids Youth Marketing Consultants: kids are "the big spending superstars in the consumer constellation," he said.

When it comes to marketing to kids, corporations have a simple strategy. They enlist the child as an agent in prying money away from mom and dad. That's why they use television time that parents don't watch, like Saturday morning cartoons, or put ads at the beginning of children's videos. And the most aggressive kid-targeted advertising focuses on the stuff parents don't want them to have--junk food and junk toys.

So while school budgets are tightening, corporations from soda and junk food manufacturers to tobacco companies are engaging in fiercer and fiercer competition for the kiddy dollar. The combination, in some parts of the U.S. and Canada, seems to have led to a marriage made in hell, in which schools and students have turned into easy marks for the corporate sales pitch.

The advertising schemes appearing regularly in schools are far wider-reaching than the old "we'll supply your school with free book covers, paid for by the ads printed on them" or "we'll give your stadium a scoreboard, but it'll have the Coke logo on it" deals. The schools, in most cases, get something more substantial than book covers--they may get a "free" computer lab, for example, or a "free" television set for every classroom. However, in some of these deals, students are required to watch television ads in class. In others, students can surf the 'net in the school's computer lab, but only visit "approved" sites, and only after seeing the ads appearing on the "approved" browser.

Perhaps the least pernicious of the corporate ad deals involves simply selling school space for ads. In 1996, the Colorado Springs school district became one of the first to formally decide to supplement revenues by offering advertising space in its schools. They sold space on the school buses, turning them into mobile billboards and allowed school hallways to fill with posters.

Since then, more and more corporate dollars have worked their way into school districts, and several of the more elaborate advertising schemes and scams have sparked major controversies. For example, several Toronto-area schools started testing new screen savers on their school computers. The screensavers mixed motivational messages with pitches for Pepsi, Coke, Burger King, MacDonald's, and Trident. The district cited budget cutbacks as the motive for the ads, pointing out that they could raise close to one-half million dollars each year from the plan.

Lin Wright, media specialist for Florida's Orange County Public Schools, said that the district has avoided using its schools as billboards in exchange for extra budget bucks. "I can't give you an official reason," he said, "but we've never agreed to anything like that."

However, Wright understands why some school officials get in bed with advertisers, although he doesn't agree with the practice. "That's a real dilemma for a lot of folks," he said. "All school systems are strapped for cash, but you don't throw the baby out with the bathwater." Advertising to kids in school, Wright said, "diverts attention from the real mission."

According to Consumers Union, which publishes Consumer Reports, more and more schools are, as Wright said, diverting from "the real mission" in exchange for corporate budget relief. The trend, according to CU, comes from three main sources: chronic school budget problems, the growing presence of commercialism in society, and the competition among corporations for the growing youth market.

In a 45-page report produced by a study on advertising pressures on children, CU observed trends such as teachers using educational material and programs in classrooms "that are produced by commercial interests and contain biased, self-serving and promotional information."

The report added that there is increased pressure on educators to "form partnerships with businesses that turn students into captive audiences for commercial messages...in exchange for some needed resource." Consequently, it said, America's classrooms, cafeterias, hallways, and restrooms have turned into display cases for "licensed brand goods, coupons, sweepstakes, and outright advertisements."

CU concludes that the trends "violate the integrity of education," especially when the marketing masquerades as educational materials. However, they warn, "when sorely needed equipment or teaching materials come only with an agreement to promote the donor's products to kids and their parents, it may be hard to say no."

A few of those "hard to say no to" items have included incentive programs by General Mills, Pizza Hut, and Campbell's Soup, such as Campbell's "Labels for Education," which urges students to push their families to buy their products. Sponsored educational materials have also found their way into the classroom, with products that would be almost laughable, were they not so tragic. Chips Ahoy has a counting game that has kids calculating the number of chocolate chips in their cookies, for example. McDonald's offers a nutrition lesson, and both Shell Oil and Chevron have produced widely distributed materials dealing with environmental issues.

Other deals schools haven't resisted include those made with Pepsi and Coke, who have fought over school vending machine markets for decades. For example, President Bush's Secretary of Education, Roderick Page, is the former Superintendent of the Houston Independent School District. While there, he arranged a five-year marketing deal with Coke. By agreeing to give Coke an exclusive on school soda sales and allowing them to advertise in schools, the district received a $5 million commission on the soda purchased by the kids.

Page is not the only school superintendent to make a similar deal with a soda company; such deals have become almost de rigueur in some school districts. For example, some Portland, Oregon high schools have granted exclusive rights to Pepsi to market its sodas on campus. In one such agreement, Pepsi contributed $17,000 for the construction of a press box for a high school baseball field, spent $3,000 to upgrade the school's electrical service (to provide outlets for the vending machines), and pledged to provide $2,000 per year in "support money" plus 40 cents for every case of Pepsi products sold on campus. Pepsi also provides $4,000 per year worth of homework planners to distribute to the students; the planners feature the company's logo on the back page.

Many people think that all those bucks going into school coffers is a great deal. However, the incentive programs probably cost the students far more than the money brought into the school district. According to a British medical journal and other studies cited by the American Academy of Pediatricians, there is a direct link between childhood obesity and soda consumption, and both obesity and diabetes has become an escalating problem among American kids. With more than ten teaspoons of sugar in the average twelve-ounce soda, it's no wonder.

Orange County (Florida) Public Schools does permit some advertising to enter the classroom: student planners, for example, are distributed to students for free, and ads for local businesses are mixed in with the calendar of holidays and sporting events. However, more aggressive advertising that targets kids, like during in-school television shows, Wright said, moves more into "kind of a gray area. Where do you draw the line?"

Some people draw the line at Channel One, the in-school television network. The brainchild of Christopher Whittle, Channel One entered the schools by offering them free television sets. In exchange for the equipment, the students would be required to watch a twelve-minute news magazine-type show almost every school day. As electronic media has grown in importance, many teachers consider television an invaluable teaching tool. Many educators embraced Channel One as a means of getting free television sets into their classrooms, and as one social studies teacher said to the New York Times, "I use it [to teach current events] because most of these kids will never read the newspaper."

Of course, no one gives televisions away for free, and the "price" of the TV sets and current events program seems small enough--two of the twelve minutes is devoted to advertising. And the value of that advertising was summed up in a statement by Channel One's Joel Babbit, who said of the company's strategy that "the advertiser gets a group of kids who cannot go to the bathroom, cannot change the stationwho cannot have their headsets on."

Not everyone thinks Channel One's deal is all that great--at least not for the students who watch the required ads. For example, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a statement calling for the control of advertising to children. "The American Academy of Pediatrics," it read, "believes advertising directed toward children is inherently deceptive and exploits children under eight years of age."

The study pointed out that, even before Channel One, "American children have viewed an estimated 360,000 advertisements on television before graduating from high school. Additional exposures include advertisements on the radio, in print media, on public transportation, and billboards."

Advertising to children is effective, the study stated, using Joe Camel as a prime example. "In two recent studies," it read, "one third of three-year-old children and nearly all children older than age six were able to recognize Joe Camel." The smoking camel, it added, is as familiar to children over six "as Mickey Mouse." The ads are effective, it concludes. "Camel's share of the illegal cigarette market represents sales of $476 million per year--one third of all cigarette sales to minors.

"There have been numerous studies documenting that children under eight years of age are developmentally unable to understand the intent of advertisements and, in fact, accept advertising claims as true," AAP continued. "Children who are developmentally unprepared to distinguish between advertising puffery and fact are equally unprepared to ferret out the 'as part of a nutritious breakfast' disclaimer on a sugary, empty calorie breakfast cereal."

Children are even less likely to distinguish between information and advertising when the ads reach them in school, the study concludes. "The placement of an ad in a school setting seems to automatically imply that the authorities on which the children rely for an education have endorsed the product."

The pediatricians' document also points out that the products most likely to be advertised to children are those they don't need, and that in fact are often harmful to them. "Television viewing has been associated with obesity," it says, "the most prevalent nutritional disease among children in the United States."

The pediatricians' document also points out that the products most likely to be advertised to children are those they don't need, and that in fact are often harmful to them. "Television viewing has been associated with obesity," it says, "the most prevalent nutritional disease among children in the United States."

Since its inception, Channel One has been attacked by liberals, by groups of educators, by pediatricians, and by conservative groups offended by its advertising of movies containing violence and sex, such as its ads for "Dude, Where's My Car?"--a movie about two potheads so stoned they can't remember where they parked.

Others have attacked on the "diversion from the mission" basis, claiming that it takes valuable time away from education. The "news" presented on the program is of the "MTV variety," according to one former student, thus "hardly worth watching." Worse still, according to professor Alex Molnar of the University of Wisconsin and economist Max Sawicky, the advertising time alone costs more than the TV sets are worth.

As Molnar and Sawicky explained, U.S. taxpayers spend about $1.8 million on the class time occupied by Channel One--12 minutes per day, nine days every two weeks. Out of that, the advertising alone costs $300 million per year, which far exceeds the total value of the equipment.

In a strategy similar to Channel One's, a computer network company, ZapMe!, offered schools an equipment-for-advertising swap that looked like a great deal: the company would set up a fifteen-computer lab in a school, complete with Internet access. In exchange, the school would agree to make sure the computers were used at least four hours per day. Also, the school would pay the cost of insuring the computers and allow ZapMe! and its clients to use the lab after school hours. ZapMe! would retain ownership of the computers, but it would also maintain them and leave them free for the school to use as long as the school upheld its end of the bargain.

From the schools' perspective, the deal seemed almost too good to be true--and it was. ZapMe! had a double-headed hidden agenda; while the kids surfed the Internet, they would do so using the ZapMe! browser, which would direct advertising at them. The ZapMe! contract also required students to bring home sponsor information to their parents at least three times a year.

Students would also be surfing with ZapMe!'s own browser which would allow them access to 10,000 approved web sites, including Amazon.com. Jim Metrock of Obligation, Inc., a non-profit, child advocacy organization that has gone after Channel One almost from the beginning, attacked ZapMe! with even more enthusiasm when ZapMe! worked its way into public schools. The computer/internet service combination, he pointed out, offered 110 video games that students could play in the lab during school hours.

Worse still, the browser included in its advertising a link to violent and self-described "addictive" video games like Doom, as well as promotions for age-inappropriate movies. The approval of the web sites, he added, seemed to have more to do with sponsorship dollars than content. "I clicked on the Amazon.com link to order movies and simply by typing 'Playboy' came up with numerous Playboy videos that most parents would agree are not appropriate for children," he wrote.

Advertising and blatant marketing aside, the company's worst offense was its market research ploy--without the knowledge or permission of students, parents, or school administrators, they monitored the kids' internet surfing, then delivered to their advertisers the data they gathered, broken down by age, zip code, and sex.

After the marketing agendas of Channel One and ZapMe! came to light, several activists' and parents' groups allied to combat marketing in schools. Commercial Alert, founded by Gary Ruskin and Ralph Nader, began heading a coalition to eliminate Channel One from the nation's schools. An ironic group of Naderist liberals and conservative organizations like the United Methodist Church, the organization has begun a letter writing campaign, petitioning schools to remove Channel One from their classrooms and asking legislators to endorse anti-commercial legislation. The controversy surrounding Channel One, fortunately, has hindered the company's growth and led to its restructuring. However, it is still in many schools, and trying to enter more.

And once the market research agenda behind ZapMe! was uncovered, an assault by parents and activist groups had an even more damaging effect on the company than did the Channel One siege, and many of their in-school activities were "zapped." The company has since restructured, changed its name to rStar networks, and repositioned itself as a satellite Internet service.

However, ZapMe!/rStar may still be up to many of its same old tricks. It offers corporations the opportunity to sponsor its LearningGate through its Corporate Adoption Program. The goal, according to the LearningGate website, is to "build America's largest Internet educational network" while offering their corporate partners a chance to "expand their educational presence on our growing network."

Partly in response to the ZapMe! debacle, a last-minute amendment to the Senate's education bill, which passed in June, limits market research in the classroom. However, with the Bush administration's pro-big business attitudes and its apparent support of voucher plans and other privatizing influences on education, exploiting the school marketplace is sure to become an even more critical issue.

It is unlikely that Bush and his sidemen will be too diligent when it comes to protecting America's kids from corporate propaganda. Tobacco advertising aimed at kids has been one of the most controversial--and most lawsuit-riddled--of advertising genres. Bush's Chief of Consumer Protection at theFederal Trade Commission, J. Howard Beales III, is an economist mainly known for his defense of R.J. Reynolds and its Joe Camel campaign. David Scheffman, new head of the FTC's Bureau of Economics, also worked for the tobacco industry.

Ralph Reed was one of Bush's advisers during his campaign and helped him gain the support of conservative and religious-right voters, even while he was actively lobbying for Microsoft. The former head of the Christian Coalition, Reed now runs Century Strategies, a lobbying firm that recently tried to defeat legislation prohibiting market research on students without parental consent. He has also lobbied for Channel One.

There is an even more frightening prospect than that of exploiting children for profit indirectly by advertising to them. With Bush's pro-privatization agenda--promoting the use of public bucks to fund private-school education and encouraging other private-enterprise forays into the field of education--the very real danger exists that our children's education will itself be tapped as a corporate profit source.

For example, the founder of Channel One, Christopher Whittle, left the organization after the controversy surrounding it hurt its bottom line. However, he has started a new business, one with the potential of becoming perhaps the ultimate kid-marketing ploy, Edison Schools. A management company which contracts to take over management of public schools, sets up charter schools, and the like, Edison is a for-profit business with investors who hope to earn a good return on their seed money.

According to analysts at Merrill Lynch & Co., which helped Edison raise $122 million in its 1999 initial public offering, the company will manage 423 schools with 260,000 students by 2005, bringing it revenues of $1.8 billion. Investors in for-profit schools have included such heavy-hitters as J.P. Morgan and Fidelity Ventures.

The Republican Party line has, for several years, promoted the idea that private enterprise is more efficient than government bureaucracy, and that private and for-profit schools could perform better on less money than public. However, one way they do that is by cutting back on administrative salaries. Another is by paying their teachers less. Certainly, an expensive private school might offer a better education than public schools, and some charter schools seem to better address the needs of small groups of nontraditional or at-risk students.

So far, however, no one has shown that for-profit schools can perform better over the broad spectrum served by public schools. Even if some do well over the short run as they buy their way into the market, the long-term prospects are frightening. What might happen when educators could begin competing for students using the kind of marketing razzle-dazzle offered by Mountain Dew commercials, or when their bottom-line objectives could drive administrators to skimp further on teaching salaries and materials?

One consistent supporter of voucher-supported private schools, John T. Walton, has also been a heavy investor in for-profit schools. Walton, the son of Wal-Mart founder Sam Walton, owns a $20 billion stake in Wal-Mart and sits on the company's board. In April of 1999, Walton invested $50 million in a private voucher effort and urged the Walton Family Foundation to give $2 million to CEO America, a company that supports private scholarship programs and lobbies for public vouchers. He recently stepped down from the board of a struggling for-profit school organization and sold his stake in the organization at a $1 million loss--after critics accused him of pushing school voucher programs to help fund his investments in for-profit schools.

It would be hard to support a claim that America's school systems are everything they should be, and with our growing dependency on technology, American schools will face greater and greater challenges in the coming decades. However, it is highly doubtful that the entrepreneurial vision that makes Wal-Mart successful--offering a broadly homogeneous assortment of stuff at bottom-dollar prices--could drive an educational organization to excellence.

The ultimate purpose of education is to help students become better at critical thinking. The ultimate goal of marketing is the opposite of that--to sell to the viewer stuff they don't need by making them think that they do. It is impossible to imagine that corporate profiteering could do anything more with education than turn our children into more placid employees and more trusting consumers. •

Morris Sullivan taught English and Social Sciences at a central Florida private school for two years and now writes freelance for newspapers and magazines. He is perhaps best known, however, as a playwright--his "Femmes Fatale," created to challenge a Florida nudity ordinance, contains the infamous "nude Macbeth."

Email your feedback on this article to editor@impactpress.com.

Make an IMPACT

Other articles by Morris Sullivan:

Morris Sullivan's Notes from the Cultural Wasteland columns

|

The pediatricians' document also points out that the products most likely to be advertised to children are those they don't need, and that in fact are often harmful to them. "Television viewing has been associated with obesity," it says, "the most prevalent nutritional disease among children in the United States."

The pediatricians' document also points out that the products most likely to be advertised to children are those they don't need, and that in fact are often harmful to them. "Television viewing has been associated with obesity," it says, "the most prevalent nutritional disease among children in the United States."